Story: Nozomi Social Welfare and Vocational Training Center for the Disabled

Staff member: Mr. Shinya Mori

Story: Nozomi Social Welfare and Vocational Training Center for the Disabled

Staff member: Mr. Shinya Mori

It was right around the time we were about to go home. The earthquake happened while we were carrying things getting ready for our end-of-day meeting. So not everyone was together in the same place.

There was a separate changing room, and some people were in there. But most people were gathered together, so we were able to instruct them to get under the tables right away even though it was shaking so much.

But the shaking was really strong, so one person couldn’t get all the way under the tables. I was nearby, so I pushed him inside and covered his head. But anyway, I was able to keep my cool at the time.

The panels on top of the air conditioner fell down from different places. There were some unbreakable dishes inside the tea cupboard, and the cupboard doors shook and moved and knocked down a few of the dishes. Our staff computers almost fell. Things moved out of place a bit, but we didn’t have that much earthquake damage.

After the shaking stopped, we checked on everyone then and there to make sure everyone was safe including our employees.

Almost everyone was okay. We did have one autistic person who had holed up inside the disabled bathroom because of the bad shaking, but we knew where that person was. We had an employee stay with that person. We were able to confirm early on that there were no injuries. It was before 15:00 when we confirmed everyone was okay.

After it shook so much, we immediately thought a tsunami would come because of all the disaster prevention education we’d received, but we couldn’t have imagined it would be this bad.

We had just started doing large-scale disaster drills at the Disaster Volunteer Center on March 2nd, so we figured we could stay out of the wind and rain here, and we had food, and even if we had to stay it would just be for two or three days. We just assumed we would be fine if we stayed here.

After the earthquake, we started putting up disaster response tents in the parking lot in front of Nozomi, and then it started snowing.

We were talking with each other saying, “We’ll probably have to serve rice too, so we’d better get ready quickly,” and then evacuees from the region came in droves.

I think it was around 20 minutes after we started putting up the tents when someone shouted, “Tsunami!!” When we looked towards the ocean, we saw electric poles snapping like sticks and clouds of dust rising.

At that time I was still thinking it couldn’t come here, because this was an evacuation center. So I was just kind of observing it. It was my first time seeing such a thing, so I was in awe you know?

But then things changed. At first I could only see smoke, but then the ocean surface appeared. Houses burning from the fires came flowing towards us, and then I knew in my gut that we were in danger too.

There were a lot of people and cars from the community in the parking lot too, so we couldn’t get out with the Nozomi cars. I tried to go back to my post at Nozomi, but then someone called my name and asked me to help an evacuee laying outside on a bed. When someone calls you by name, you think you have to help them first. There was no time to think about my work priorities with the tsunami coming, anyway. So I was trying to get the person on the bed to a safe place while watching the tsunami coming.

I was afraid, but I was trying to get this person to safety because I felt I had to help. Then I was also entrusted with an old man with poor eyesight. Since I had to help him along, I was slowed down no matter what I did, but I tried to evacuate with them to the mountain behind the parking lot. At the time, the tsunami had already started flowing into the parking lot.

It came that far in the 15 or so minutes after I noticed there was a tsunami. I ended up getting swallowed by the tsunami, but somehow it brought me to the mountain behind the lot. Then after around 10 minutes or so, the waves pulled away and we were saved.

After helping rescue people around the mountain, I was worried about Nozomi, so I went back. I hoped there was no one left at Nozomi. It was a pile of wreckage, but I went inside and called out checking the rooms one by one. It seemed like no one was there.

Then as I was headed towards the entrance of Shizugawa High School on the mountain, I ran into Mr. Hatakeyama (a Nozomi employee) and asked about the situation.

He told me, “Everyone is soaking wet, but they’re safe in the high school biology lab. We did confirm that one trainee died at Nozomi, but we had to help ourselves and make sure our other trainees stayed alive, so we evacuated anyway. Yet, there is one more trainee still missing.”

It was also getting dark, so we agreed to just help everyone who was with us at the moment and went to the high school’s biology laboratory.

Nozomi’s employees and disabled trainees were there along with other people from the community. The room could fit around 30 people.

For the first night, we had the biology laboratory assigned to us. People from the Minami-Sanriku Social Welfare Council, Nozomi, and retirement homes had all evacuated to the school, and the teachers decided they should assign each group a room. They got us the rooms the next day. I think this was the morning of March 12th.

What saved us was that they had water. They also passed on all the information from the radio because there was no TV or anything.

Around midnight on March 12th, rice balls were distributed. A key person from the Minami-Sanriku Social Welfare Council and the school staff paid special attention to our trainees and got these rice balls especially for us from the Asahigaoka housing complex north of the high school. We were grateful for that.

The first problem we had was food. We were also afraid we could die of weakness as we were wet after being swallowed by the tsunami. There was a stove that saved us because we could get warm. Otherwise things would have been much worse.

Then, one of our disabled trainees needed to use the toilet. The area in front of the biology laboratory was the school yard and it was full of cars, so there was no place to go. I remember the school made a temporary place for us at the back of the gym.

Pretty soon the women needed to use the toilet too. We made a toilet and gave them privacy by using the desks and curtains in the classrooms and turning off the lights of the cars in the yard. But it was cold and there wasn’t much privacy, so they didn’t feel comfortable and couldn’t go even though they had the urge.

I think they were trying to be strong. A few of them had injuries from debris hitting them while the tsunami attacked, but we were able to evacuate without any major injuries that stood out.

No one really made a big fuss. I imagine they probably felt in their gut that something major had happened, so everyone just cooperated without complaining. It also helped a lot that we had the room set aside for us.

There were also non-disabled people from the community there with us, around 3-4 of them. Those people also responded with understanding.

We ended up staying at Shizugawa High School from the night of March 11th to March 18th, about a week. What concerned us was that some trainees were saying they didn’t want to leave the high school, because they were worried that Nozomi, their gathering place, was gone. Some of them asked when we would meet again, and that left an impression on me. Some of their parents asked the same thing too.

Because of this disaster, we unexpectedly ended up living as a group, even sleeping in the same room for a week at the longest.

They felt at ease there because they were with people they could trust.

Some families said the hardest part was after the group left the high school and each family moved to different places.

After they moved, we employees visited all the trainees at their respective evacuation centers. Then they would light up with this knowing look and say, “Mr. Mori is here!” or “Mr. Hatakeyama is here!” But when we left they would have to face reality again and got depressed.

Some families asked right away, and some asked after a few visits, but the whole time we were asked when we would reopen.

We went to see them individually although it was on different days, so we saw almost everyone, but our disabled trainees themselves couldn’t leave the places they were staying, so they didn’t know if everyone else was all right.

Mr. Hatakeyama and I talked about looking for a place to reopen in the Iriya area (an area in the Minami-Sanriku-cho valley). Not that we had any prospects.

After agreeing to keep checking on our trainees and look for a place to reopen, we left the evacuation center on March 18th.

Mr. Hatakeyama and I started working again on March 22nd. Our foundation’s car was fine, so we used that to get around. We were really grateful that Kesennuma City designated vehicles belonging to foundations as emergency vehicles early on, so we got priority access to gasoline.

So I would meet with Mr. Hatakeyama every morning, and we would go around visiting our trainees in different evacuation centers.

Meanwhile we found a location to reopen in at the end of March.

The whole while, as different problems came up, like being unable to get a prefab building, we made a list so we could ask for assistance later.

In the rush to build temporary housing, we did manage to get a prefab even though it was just a rental, so I guess it did go smoothly.

But I think it took a long time from our trainees’ point of view. Every day was long for them. It’s easy for us to say it went quickly, but I think it felt longer to the people in evacuation centers.

I think it was around mid-April when we made a suggestion in order to get our trainees together as they were all scattered in different shelters. They couldn’t bathe at the shelters, so we decided the employees who were available would take the trainees to a bath house 2-3 times a week in Naganuma, Tome City. They just went to take a bath and have a meal. Though it wasn’t everyone.

We did that in April and May, mainly with the trainees living in evacuation. We had no place for everyone to gather, so we went on this way until we reopened in Iriya. It wasn’t everyone all the time, but we were able to get together at the bath house.

It wasn’t actually designated, but we had one evacuation center especially for disabled people. Social workers, disabled people, and their families who had lost their homes lived together in the mornings and evenings, and during the day they continued their activities as usual. The family members also went to their jobs and such from there.

Non-disabled people from the region also evacuated to our other facilities, and some of them stayed until August at the latest. Those facilities also asked Kesennuma City to support them as evacuation centers for the disabled, and got special public aid.

Those facilities shared their supplies with Nozomi, so we distributed them to our trainees living in shelters.

Around the time of the Golden Week holidays in May before we reopened, we learned about JDF (the Japan Disability Forum). These people wanted to help the disabled. We had them plough the fields with us when we first reopened in the prefab in Iriya in late May.

The JDF people came from all over the country, all the way from Hokkaido in the north and Okinawa in the south.

We set up a map of Japan and filled in the prefectures people had come from. We wanted to thank the people who’d come to support us, so we later sent them our newsletters that showed them how well Nozomi was doing.

Before the disaster, most of our work came from local companies that outsourced to us. There were maybe a dozen or so companies. We didn’t make our own products.

There wasn’t immediately any work to do when we reopened, so we just kind of celebrated being together and decided to do whatever was in front of us. So we started working in the fields. Not everyone was used to the work, but we just had to do it.

But on rainy days, there wasn’t enough space in the prefab for both the employees and the disabled trainees to fit sitting down.

So when it rained, we just went out somewhere. Normally it’s the other way around, but that was how we lived.

Now that we had a place to get together, some people were seeing each other for the first time in a while, so everyone was smiling. There were different people coming from JDF each week too.

Some of our trainees’ family members were also glad to have a place they could leave the trainees during the day, since temporary housing procedures had started around that time.

When Mr. Hatakeyama and I thought about the future, we knew the trainees couldn’t work in the field in winter, so we had to find something for them to do indoors. Then someone just happened to suggest paper making.

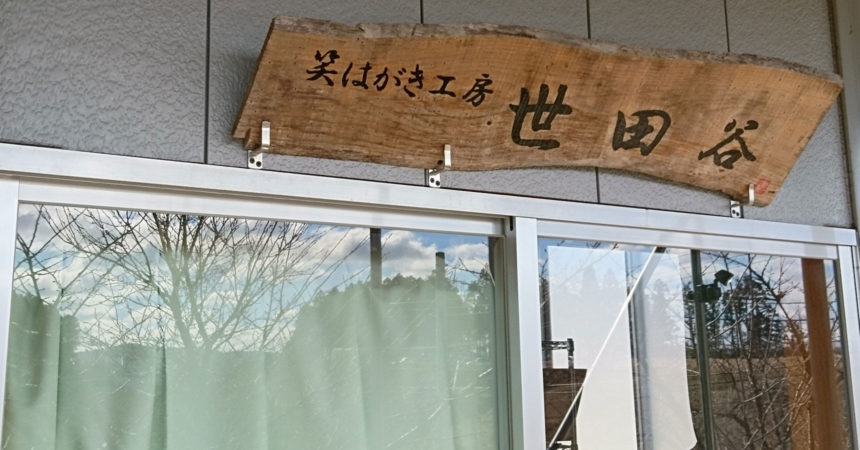

When staff members from the “Sendai Te o Tsunagu Ikuseikai” Foundation came to visit, they gave us a set of paper pressing and stenciling tools. After we had begun making paper, the “Setagaya Lions Club” social services group also provided a paper pressing machine.

We moved to the next prefab in November before it got cold. It was a little bit bigger than the one in Iriya. We could all fit inside on rainy days, and there was heating, so we were relieved we could get through the winter.

So the things we had to do kept expanding, but for the first two or three years it was kind of chaotic. We all just sort of kept going without getting ourselves organized.

Of course there were also times when we solved various problems on our own. But there were lots of people thinking of us, so sometimes it seemed to me like things were decided more by the people who came to help us than by us.

We really met some amazing people, and they came at just the right time to support us. Not that we didn’t notice it at the time.

I think it was the same for our trainees. Myself and Mr. Hatakeyama suddenly brought in all these people, and before our trainees knew it we had a paper pressing machine. It wasn’t so much of their own accord as that they were almost forced into it, but they sensed what was happening and said, “We’re doing this!” I think they just adapted to the changes that were happening every day.

With the stencils we first received, it wasn’t like the product would come out the same way no matter who used them. Paralyzed people needed support, for instance. So we had to find our own ways to help them use these tools as we watched them.

As we kept devising ways and means, one of our trainees became really motivated after we got busy with the paper making. He used to take off work a lot to help with his family farm before the disaster, and it would have been fine for him to keep spending time on that, but he still came to Nozomi every day and confidently said, “We won’t get it all done if I take time off.” I realized he was taking pride in this work.

We didn’t do this all on our own. Some people found us directly or through Nozomi families to help.

It was like someone always connected us with someone else. We didn’t actually do much to seek out help on our end.

We were just there, and people came. We were really blessed. It was miraculous, like people were drawing in more people to support us.

For the first two years or so, it was like we had guests almost every week continuously.

In Minami-sanriku’s case, the town mayor had appeared in the media, so we had some publicity. That put a spotlight on us, which I think was part of what brought so many people to help us.

Sometimes I wonder if things would have been different if we’d been in a different place at a different time.

It depends on the person, so we can’t do it with everyone, but we sometimes do talk about the disaster with our trainees.

One person who used to be absent a lot before the disaster started coming to Nozomi every day after entering temporary housing, but then started being absent again as soon as their house was rebuilt.

With people like that it’s sometimes better to help them remember the momentum they had right after the disaster, but there are also people it’s best not to breach the subject with. It’s hard to judge.

It’s fine for the trainees who are communicative enough to express their feelings, but you never know how it was for the ones who don’t talk about it.

Some families have told us their disabled family members have had nightmares since the disaster. So it’s affected them in different ways. We’ve come this far with all the care we could give them, but they also need our support with post-traumatic stress disorder. We haven’t provided enough of that, I’m afraid.

JDF volunteers were coming every week, and the trainees started opening up to them. They started telling those volunteers about their experiences, because all they could talk about was what they themselves had gone through.

I feel like this helped our trainees grow. They would be telling the exact same story to a different person, but they would tell it differently from the previous week.

You might speak about the same experience in a different way as time goes by. That’s natural, whether you’re disabled or not.

They had this invisible trauma from the disaster, but as they talked about it they were healed and learned to accept the experience more.

For example, this is something I think still gets to a lot of our female trainees. After the disaster, they started carrying a lot of things around because they’re worried an earthquake might come while they’re out. We see that, and we realize it’s still affecting them. Because their houses were washed away and their treasures disappeared.

But as they talked to different people each week about the feeling of losing their homes and other important things, they eventually began to accept it.

They couldn’t accept it at first, but as they continued talking to the different people who came each week, they were able to digest it and overcome it gradually. Though of course there was no changing what had happened.

One trainee who used to have trouble communicating with people of the opposite sex now enjoys taking photos with them after repeating the process of asking people to be in his photos. He matured and got better at communication.

I think it was a really precious experience for our trainees because they could learn while interacting with others after the disaster.

We’re still operating in the prefab building, so I think we’ll only really be able to say we’ve recovered once we have a headquarters, or you know, a proper building. I think the completion of that building in spring 2019 will be a crossroads for us.

But the completion of that building won’t be the goal. We’ll still have to keep going one step at a time. We have to keep treasuring not only the building itself, but also the great assets we have, including the people we’ve met along the way.

The JDF volunteers who came at the time of the disaster said they would keep coming for ten years, and I think that’s incredible. So it’s important not to forget the warmth of the people who always take care of us, too.

I truly admire their deep commitment, as I don’t think I could go to the same length for others if I were them. I’m still in over my head with what I’m dealing with now, but one day I also want to commit myself to helping others like they’ve helped us.

We’ve been influenced by all these people, and we are thankful for all the experiences we’ve had that have led us in a good direction.

Thanks to the liaison meetings for disaster affected vocational support centers for the disabled, we were connected with the Able Art Company (now Able Art Japan), which shares the artwork of disabled people with communities. They admired Nozomi’s passion, and with them we decided to create something combining paper making with a symbol of Minami-sanriku.

Since the Moai statue was coming to Minami-sanriku again, we had our disabled trainees draw Moai illustrations, then choose one drawing to make into products. Able Art Company then started by making towels. The project moved along at a steady pace after that.

But we can’t rely too much on these Moai goods as our leading products. We have to develop new items to expand our product scope, or our sales will peter out.

This is a severe world, and it might be naive of me, but I do hope to pass on this legacy to society. These wonderful goods produced by disabled people were actually co-created with so many people who have supported us.

My ideal is for people to pay for the products simply because they’re good products, not out of sympathy for disabled people. Then afterwards I want them to be like, “Wow, this was made in a place like that!?” Those are the kinds of products we want to make.

A lot of our trainees aren’t used to being recognized, so by having them create these products, we hope to break down misunderstandings and spread awareness about disabled people. We want to show people that actually, there’s not much disabled people can’t do.

All people hear is the word “disabled,” and they immediately think it must be awful.

No matter how hard we’ve tried, there are still things people just don’t properly understand about the reality of disabled people, and that’s our challenge. So we’re doing our best to increase social awareness through our sales of these paper products for that purpose.

We hope to continue to grow along with our trainees, without forgetting to be grateful for everyone who’s gotten involved with Nozomi.