Story: NPO Midorikai, Local Activity Support Center (Vocational support center for the disabled), Midori Workshop Wakabayashi

Director: Ms. Mariko Konno

Story: NPO Midorikai, Local Activity Support Center (Vocational support center for the disabled), Midori Workshop Wakabayashi

Director: Ms. Mariko Konno

What were you doing at the time of the disaster?

That day was a recreation day at the workshop. Our activities normally go until 14:40, but recreation ended a little early that day, and the earthquake came when we were taking a break around 14:30. We were just resting on the sofa at the time.

Our disabled trainees were just really shocked, but they didn’t panic or anything.

How did you deal with the shaking, and what were the damages?

The lights in the room where we were resting were made of glass, so we had the trainees avoid those and take refuge elsewhere. There were some people in front of the dish shelves as well, so we guided those people to a safe place.

We had been doing regular evacuation drills at the workshop long before the disaster happened. We also had things posted on the walls so people could visually see which places in the workshop were safe, and which were dangerous.

We had always maintained that sort of disaster prevention awareness. On that day too, everyone responded based on our previous drills and preparations.

Besides securing safe places and confirming unsafe places in the workshop, we had also secured all the shelves in the facility. Thanks to these preparations, not a single person was injured, not a single thing fell over, and we incurred no damages from the earthquake.

What did you do after the earthquake stopped? Were you aware of the risk of a tsunami?

We had thought about the risk of a tsunami. But although we were aware of it, we could have been more thorough in securing a safe place to evacuate.

We did anticipate the risk of a tsunami.

So you started giving directions to evacuate right away?

Yes. That’s right.

And your trainees followed your directions and started evacuating as a result of your daily drills?

Yes. Things went smoothly up until that point.

I hear you evacuated to an elementary school. Was that the established place you were supposed to go in the event of a tsunami?

Yes. We started by evacuating to our local Arahama Elementary School.

The evacuation location for Midori Workshop had been decided since before the disaster. But since we understood the risk of a tsunami, at that time we were still trying to determine a place that was guaranteed to be safe in consideration of that risk.

We had asked a disaster prevention expert about how to evacuate from a tsunami considering Arahama’s terrain, and were told that the structure of this region could cause a tsunami to rush in like a river.

There is a gas station at the end of a straight road from the swimming area on the beach, and buildings carried by the tsunami actually went crashing into it.

So the gas station filled up with debris, and when the second tsunami came in like a follow-up attack, the direction of the waves changed. So then the waves split up and went towards Shinmachi 2-chome, where our workshop is.

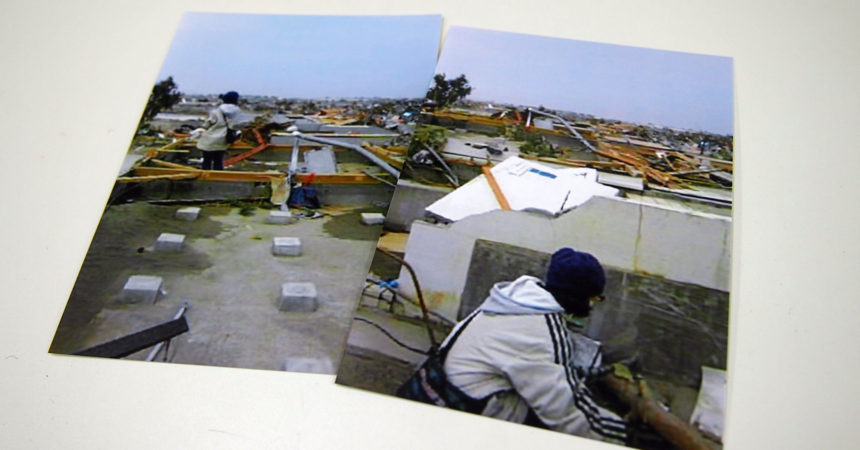

So that’s why our workshop building was carried off by the tsunami, and now there’s nothing left. The houses that remained safe were located slightly away from the tsunami’s path when it rushed in like a river.

We had thought about how to evacuate, but at that time we were still considering whether or not we should evacuate to Arahama Elementary School, which could be in the path of a tsunami. We hadn’t yet reached the final stage in deciding where exactly to go to escape a tsunami.

Did you go on foot to your first evacuation location?

We went both on foot and by car.

What was your process for evacuating?

There was a community center near the workshop. Behind that there was a park.

As we were going to evacuate, we heard the information that maybe wide spaces like parks with nothing in them would be safer.

Some people had evacuated to the park. When it’s shaking that much, you do feel like it would be safe someplace where there are no buildings and nothing to fall over.

If the earthquake had happened when we were supposed to go home from the workshop, our trainees might have decided to go to the park on their own judgment.

It’s scary now to think that if it had been left up to each person’s judgment, they might have just followed anyone who asked them to go along.

How many disabled trainees did you have when you evacuated?

That day, we had 7 trainees with us. Six of them evacuated with us. One person had already gone home before the earthquake happened, because the recreation had finished early. We evacuated with the trainees who were with us in the workshop.

Around how many minutes after that did the tsunami come?

After that, we fled not to Arahama Elementary School but to another elementary school inland, so we didn’t actually see the tsunami.

Was the decision to flee to that inland elementary school also a “just for now” type thing?

Yeah. The information we heard from the radio on the height of the tsunami was also changing by the hour.

Arahama Elementary was already very crowded when we got there. We couldn’t get into the school grounds by car, and traffic was jammed around the school. For those reasons, we took refuge in a convenience store near the school.

There was a heavily trafficked prefectural road nearby that was also jammed, and we thought there was no place for those people to evacuate but Arahama Elementary. We were worried that all the drivers on this busy prefectural road might not be able to fit inside the school, and so we waited in the nearby convenience store for a while.

The prefectural road was in front of the convenience store, so we could see the traffic jam right before our eyes. We started thinking about where else we could evacuate to.

Then the information on the radio changed, and they said a 10 meter tsunami was coming. A 10 meter tsunami means the only safe places are on the 3rd or 4th floor. So we decided it was too dangerous to stay where we were.

Four kilometers beyond Arahama is Shichigo Elementary. I remembered they were doing construction there a few years back. They said they were fortifying it against earthquakes. So in consideration of safety, we decided to evacuate to Shichigo Elementary instead.

Around how long did you stay at Shichigo Elementary?

We were there for 10 days after the earthquake with our trainees.

Were you able to secure a place to stay?

We were able to get into one of the school’s rooms. There just happened to be some people from the same Arahama area there. When we went inside and found some places to sit down for the moment, they were there next to us.

How did the trainees do in the evacuation center?

I think they were worried, but they looked calm. When I asked them why, they said it was because they had done evacuation drills at the workshop, and they knew I had been studying disaster prevention for a long time, so that helped them to feel a little more at ease.

I took a disaster volunteer coordinator course as part of my studies. A volunteer coordinator is a person who takes a leadership position to manage people who come to volunteer at an evacuation center in the event of a disaster. The coordinator needs to have knowledge of disasters, the types of needs that can arise, and how to manage an evacuation center. I learned how to run a reception desk and manage a shelter through role playing.

For example, in this course you learn how to use damaged homes and whatever you have to rescue people and keep activities going when you have no proper equipment, how to get past this kind of situation, how to manage a shelter, and so on. I had been interested in disaster prevention for a long time, and had been learning about it for a few years.

Long before the disaster happened, I often told our trainees about what I’d learned. I think this accumulated so the trainees themselves felt like they would be fine because I had studied these things.

So at that time they often asked me what they should do next.

I really feel glad I studied all this. I had thoroughly prepared disaster prevention equipment and secured all the furniture because of what I’d learned, so not a single thing fell over and no one was injured.

If even one person had been injured then, we would have been late evacuating because we would have had to tend to that person, and I think the tsunami would have gotten us. And if you let the people who are okay evacuate first, you end up splitting into a few groups. I think our initial response was good because we were able to evacuate without a single injured person. In some ways my preparations and learning paid off.

What inspired you to start your studies?

It had been common knowledge for many years that an earthquake would happen in Miyagi Prefecture, so I had a personal interest in disaster prevention studies. We have to protect our trainees, so it was natural that I was making all these preparations for disaster prevention.

What were the 10 days in the shelter like? Did you have any problems?

Hmm. Well, everything was a problem. Our trainees and staff weren’t able to receive or transmit the necessary information. We were isolated, and couldn’t contact anyone.

We staff need all kinds of information to protect our trainees to get them home safely. We need information about the situation around us, like if the buses are running or not, how and where to obtain medicine, and so on. We had difficulty making surefire plans on site without such information.

I think it was also really stressful for our trainees because we couldn’t secure personal space for them in the shelter.

Were you sharing a room with abled people the whole time? Was there any trouble?

Yes. We shared a room with abled people for 10 days. Though the evacuation center made no special arrangements for our disabled trainees, we didn’t cause any trouble for the people around us.

Because the local people from the same Arahama area were understanding?

Yeah. We had a good relationship with the former neighborhood association chairperson who happened to be in the same room with us, and thanks to that connection we got along well with the locals who didn’t know us as well. We also talked proactively to the people in the room, so we were able to get to know each other and support each other without any trouble.

How was your relationship with the shelter management?

The school teachers took the lead at the shelter. We communicated proactively with them, and told the teachers about our situation as social workers.

Did you get any special consideration from the management?

Not really. But everyone was in a state of confusion when the disaster happened, and if we had just expected others to support us, I don’t think it would have gone well. In a disaster, the people who support you are all in the same position. They’re evacuees too.

If we hadn’t gotten involved in managing the shelter ourselves and had the mindset of doing it together, I don’t think things would have gone well for us at the shelter.

So after we took refuge at Shichigo Elementary, we went to the faculty room right away and talked about what the situation was, any information to be shared, how we could contribute, etc. Through such communication, we naturally got involved in management.

What was good about living in the shelter? Anything that helped you?

Our trainees were really amazing. Abled people generally can’t help feeling like disabled people are coming from a position of weakness. Unfortunately this is the usual way of thinking.

Our trainees do have difficulties in life because of their illnesses, and so they do have a tendency to sort of hold back.

At that time, I think everyone felt like they had to do something in that situation.

There’s a retirement home called “Shioneso” in Arahama. Some residents of that home evacuated with us, and our trainees helped those people get up to the second floor.

I think there’s something to the idea that you become weak if you go in expecting to be protected. In a situation like a disaster, however, those who can move should do whatever they can do. There were a lot of elderly people in the shelter, so our trainees helped clean for them and carried meals to the 4th floor for elderly people who had trouble walking.

They also took initiative to start fires for everyone, to boil water for babies’ milk and things like that. Our trainees joined in these tasks of wood chopping and fire building, and I am very proud of them.

I think people, myself included, tend to think negatively when they’re feeling down emotionally.

In a situation like a disaster, I think it’s better to take some sort of action yourself so you can see things change a little.

Most of the people staying in the shelters during the day were elderly. The younger generations left the shelters for work in the mornings.

And so the elderly people who stayed at the shelter got bored during the day. Disabled welfare organizations like us have a lot of young trainees, and there are all kinds of things young people can do, not just physical labor.

For example, elderly people normally don’t use cell phones. But in a disaster situation like this, you have to use a cell phone to contact people. Our trainees did what they could by teaching elderly people how to use cell phones.

Normally it might not mean much, but this kind of support is really helpful in a disaster so people can contact their families to make sure they’re okay.

They would ask questions like, “How do you do this?” And “Where is my daughter’s contact information?” So our trainees taught them how to open their contact lists. When these elderly people got phone calls, they didn’t know what button to press to answer, and so we helped them together because we were nearby. This really seemed to be a big help to these elderly people.

These everyday things seem so simple, but I don’t think the volunteer helpers or school teachers at the evacuation center could have done this because they were so busy with general volunteering and management. We were able to help because we were there, spending every day in the same room with these elderly people.

Did you release your trainees starting with the ones whose families you could contact?

That’s right. Some were picked up by their families, and we took others in the workshop car.

Ten days later, everyone was gone

Our number of trainees staying in the shelter every day decreased, until finally there was just one person left. Because of various circumstances, this person was doing her best to live on her own in the region. Her apartment was half destroyed, and because she was sick and disabled, we wanted to make sure she was able to return home and had the necessary support before leaving the shelter.

During our ten days living at the shelter, we worked with her to make sure she could go home with peace of mind. It wasn’t perfect, but things fell into place ten days after the disaster.

Afterwards, she would have to live by her own means after returning home. Our staff also had other trainees to deal with, so we weren’t in the position to support only her.

First we brought her to her regular physician, and then we also helped her tidy up her apartment so she could make a smooth transition back to her ordinary routine after returning home.

She couldn’t find her bank book and cards in the house, so we went to the bank together to have them reissued and went through all the procedures to make sure she didn’t have to worry about money, to make life just a little easier for her.

Of course the workshop continued to support her after she left the shelter, but we suggested she try living on her own first, and released her from the shelter with her consent.

How were your trainees doing when you released them, and how did they feel about the workshop?

At the time we left the shelter, only one of our trainees was aware that our workshop in Arahama had been washed away. Because we evacuated immediately after the earthquake, and there was no way to know. It was the same for the trainees who didn’t come to the workshop the day of the disaster.

During our ten days at the shelter, we went to Arahama with the last trainee who remained and confirmed that the workshop had been completely washed away. So that trainee and we staff were the only ones who knew.

The other trainees probably only heard what was on the radio, so I don’t think they were really able to sense that the workshop was gone. I think our trainees in the shelter felt relieved at first just because they were able to go home and their families were alive.

On March 30th, the trainees and staff who were able to come went around and reported on the status of the workshop. At that time, everyone knew about Arahama from the newspapers and such.

I guess because people already had an idea of the situation in Arahama, when we told them the workshop had been washed away and only its foundation was left, they were just like, “Oh, I see.” And they didn’t say anything more.

We also reported to our trainees that our farmland had been flooded and was unusable, that neighbors had died, and that all their crafts and materials had been lost.

We figured reporting the situation was the place to start. Our trainees are the focus of our organization, so it wasn’t just about the intentions of the management. We didn’t want to rebuild on our own without consulting the trainees.

So after explaining to them that we had no support, only two staff members, and no funds to rebuild now, we asked our trainees, “We have no idea where we would rebuild it, but should we rebuild the workshop?”

Then our trainees said, “Let’s build the workshop. We need it.”

With that sentiment, we reported to the city government and our foundation that we were going to rebuild the workshop, and started taking action.

It was important to us to move forward alongside our trainees.

What was the next step after you decided to move forward with rebuilding?

We couldn’t build the workshop right away, so we figured we should just find a place we could all gather first.

Because we had no more workshop, we had to suspend our trainees’ activities for early April.

And we would visit our trainees’ homes, or everyone would gather in the park. We staff sometimes had meetings on the benches outside the supermarket.

We had to find a temporary place to get together, so we started looking around, but our problem was we didn’t have the funds to rent a place.

We petitioned the city government, and for a short period from around April 17th to the end of May, we were able to borrow one room in the disabled welfare center. We used the mornings to get everyone together for activities, and in the afternoons we searched for new locations and went around greeting people.

By April, our business partner from Arahama had already resumed their business. That company had also suffered major damages from the tsunami, but even in those circumstances they reached out to us, so we staff and trainees volunteered to gather up the company’s equipment that had been washed away by the tsunami and was covered in mud, and wash it with a pressure washer.

After that we also started preparing for activities at the workshop, wondering if maybe we could make crafts or find something else to do. We were really grateful we were able to continue our relationship with our business partners even though our workshop was destroyed.

We were only able to borrow the room in the disabled welfare center until the end of May, so we were also property hunting alongside our activities. Our trainees seemed to notice how hard the staff were working to prepare to rebuild, and they asked us of their own accord if there was anything they could do. And so we thought of something they could do that wouldn’t be too burdensome, and asked them to search for properties.

But during the property search process, they repeatedly heard prejudiced statements about disabled people.

Unfortunately I think the real estate agents and property owners were worried there might be some sort of trouble with an organization for disabled people. We hadn’t done anything to deserve such criticism and humiliation, so it was sad. I wished people would be more understanding of social welfare organizations.

When we went to see real estate agents with our trainees, they would refuse to rent to a facility for disabled people. Right in front of our trainees, they would say, “We could never rent to disabled people.” I don’t ever want to have such a sad experience again.

It was really hard until we secured our current property, but I think it was a really good thing that we did this along with our trainees.

We somehow found the Wakabayashi building we’re in now, and opened on June 7th. But our contract with the disabled welfare center was until the end of May, so we had to suspend our activities for the 6 days until our opening, although we felt bad for our trainees. They were understanding about this. During that time we did consult with them over the phone.

It’s because we worked together with our trainees until our reopening that we know the value of our workshop and of everyone who’s cheered us on. And because our trainees searched for properties with us during that process, they now feel like this workshop belongs to them.

How did your trainees’ work change after you reopened?

There were major changes in our activities. In Arahama, our main focus was agriculture. We had been farming in a field around 3 square kilometers large, but the tsunami destroyed our field, so after that crafts became our main activity.

Our trainees accepted this willingly, because they knew it was all they could do in this situation. They were happy just to have something to do. I don’t think it’s about what exactly the work is. I think they were just happy to have something they could do while spending time together. Because they’ve always been close.

So did the trainees get a stronger sense of the value of their work?

Yeah, well I don’t know about work, but I think their way of thinking about life itself changed. For them I think that change was a real strength, and a significant change in their lives. They said so themselves.

Sometimes when you get sick, your relationship with society changes. Mental illnesses especially aren’t very well understood by society, and sufferers can be forced to quit their jobs because of their condition, or become isolated from their friends. They might not be able to build healthy relationships with their families, and many concerned people have very difficult experiences.

Some of them feel alienated, or become very negative thinking there’s no more hope for them because they’re sick.

But even though some of these people saw themselves negatively before, through the disaster they were able to find a role they could play in that moment and improve their self-esteem. They realized they were one step ahead just by being alive, and they were grateful.

The idea is that they were starting life from square one rather than square zero. That’s a big difference in thinking. They’ve become more positive, you could say, and have learned to value themselves more. Such realizations and changes in self-perception are something that’s difficult to bring about with our support alone.

When you come to your own realization about your existence, that belongs to you. The disaster brought on that realization.

These sorts of changes brought about by difficult experiences are an invaluable source of strength for our trainees’ future lives.

What are your thoughts about your current activities?

We still have a long way to go. We’ve only just now established a basis for running our organization, including our activities.

We ended up at our current location with no other options, so we would like to look for our next base, but it’s quite difficult and there are a lot of issues. We faced prejudice against disabled people when we were looking for our current workshop, after all.

We found the building we’re in now through a real estate agent who was understanding of our organization, so we were grateful. We were introduced to this agent by a key person in the neighborhood we’re in now.

When I look back on it now, I realize we were accepted by our neighbors right away in Arahama where our previous workshop was located, and I’m really grateful for how kind those people were.

And so this time around I’ve realized how severe society’s judgment is. It’s sad to think our trainees face judgment like this every day.

Do you have any thoughts or things you want to share now?

Since that disaster, we’ve had opportunities to talk about our experience and how we prepared ourselves.

Of course, other welfare organizations located near the coast around Japan are worried that the same sort of disaster or tsunami might happen to them.

I have been invited to speak around the country for a few years now, but I sometimes wonder if my speeches are actually raising people’s disaster prevention awareness, and if people are actually putting what I say to use.

The Kumamoto earthquake was a big shock to me when it happened. I have passed on our earthquake experience and the things we did to prepare in the hope people might put it to use. However, I’ve seen how people have had the same experience in Kumamoto and various other places, so I feel like my efforts haven’t been useful.

Whenever I hear about a natural disaster, I feel really frustrated. I know this isn’t a small problem that can be solved by someone like me telling people about it, but that doesn’t change how I feel.

People’s memories fade too, and every day I think about how best to appeal to people around Japan to overcome the awareness problem, how to protect their lives in the event of a future disaster, and how to help them better understand the challenges social workers face in a disaster.

Ultimately, the only thing I can do is talk about it like this.

First, I hope that learning about our disaster experiences will be the first step for people to change their way of thinking and come to new realizations.

Social workers do face different challenges in a disaster than lay people do, so I want people in the social work field especially to understand this. Because both our trainees and our staff went through a really hard time in the disaster, and I don’t want our peers around the country to go through the same thing if a disaster happens to them.

After the disaster, a welfare organization located near the ocean in another prefecture once came to us saying they’d like all their employees to hear our workshop’s story. Later I heard that they started taking disaster prevention measures based on our experience.

I feel somehow relieved when I hear that a social welfare organization is now putting the things we told them to use to make preparations. It’s also really great when the organization doesn’t just copy the preparations and responses we adopted to protect our trainees, but discusses things amongst themselves to arrange their own strategy. It’s scary not knowing what might happen.

The real estate agents discriminated against us, but on the other hand I also think the people of this world are truly kind. I felt that way at the shelter.

Some people were like, “What do you mean, disabled?” because they just didn’t know, and so when our staff stepped in and explained it to them, they were just like “Oh okay,” and naturally accepted it. I think one of our roles is to be like coordinators who connect with people who aren’t yet aware of disabled people and their conditions.

I experienced that living at the shelter. I asked our trainees if it was okay to tell people about their disabilities just in case they needed help, and after obtaining their consent, I told the abled people in the shelter.

Once when one of our trainees was taking his medicine, someone asked us, “Is that guy feeling sick?” It seemed they were just curious. When we answered, “He’s taking his medicine from his psychiatrist,” the person was like, “It doesn’t seem that way. I couldn’t tell.”

When we step in and explain like that, they feel at ease and want to learn more about disabled people. Then they even help watch over them. That’s really nice. It’s mutual understanding. It’s important for people to know.