Story: Ms. Chie Matsuda (woman/ age 40 at the time/ hearing impaired)

Story: Ms. Chie Matsuda (woman/ age 40 at the time/ hearing impaired)Ms. Chie Matsuda

Story: Ms. Chie Matsuda (woman/ age 40 at the time/ hearing impaired)

Story: Ms. Chie Matsuda (woman/ age 40 at the time/ hearing impaired)Earthquake

Where were you and what were you doing the day of the disaster?

I was at my workplace in the Shishiori neighborhood. I was working at a company in the fisheries industry. They had around five factories total, but they were all destroyed, and now the company has downsized and integrated, so I’ve been laid off.

What sort of work did you do for the company?

I did shipping, packaging, assembly, and so on.

Around how many years did you work there?

I was there a long time. Eleven years.

Were you living in Kesennuma at the time?

I was living in prefectural housing in Shishiori, in the mountains.

When it started shaking around 14:46, did you get the feeling this was a bit unusual?

Yeah I did. It happened during work, so first everyone gathered in the courtyard outside the factory. The department supervisor took attendance and made sure everyone was there. There were around 100 of us. After that, we all followed the supervisor to evacuate.

Was the factory on low ground?

Yes. The cars in the parking lot in front of us were shaking and rolling on the waves. I felt kind of dizzy, and there was no way to hide under a table or anything like that, so I just stayed standing and thought, “This is not normal. It’s strange; the shaking is too strong.” At that time, I wasn’t aware a tsunami would come, and of course I couldn’t hear sirens or anything either. At first I was worried the second floor ceiling might fall down and crush us, but then I just wanted to get out of the room. A pipe had burst outside the window, and I could see water gushing out. I really had no idea what to do, but our supervisor said, “We can’t go outside now, so just take anything valuable and get ready,” and so we waited. After that, we evacuated. I was just worried that the building would come crashing down, and I was relieved to be able to escape. Once the shaking stopped, I wanted to go home, but around 15:00 my coworkers told me, “You can’t go back, it’s too dangerous. You should wait here.” I wondered why, because I still hadn’t imagined a tsunami coming. It was around 15:30 when I learned the reason. When I actually saw the tsunami before my eyes, I thought, “Oh, because a tsunami was coming. That’s why they told me to stay here,” and I understood. After that, I watched the tsunami rushing by with my coworkers. I saw a big ship being carried from the sea at alarming speed, and I watched it wondering how far it would go. A lot of other things came floating past too, like still intact houses and cars. I thought, “The factory and my car must be all gone.” Everyone’s legs started shaking, and we understood we couldn’t go home.

Was the place you and your supervisor and coworkers evacuated to on high ground?

Yes. The road was too narrow for cars to get through, so we all fled up there on foot. It was around 5-10 minutes away from the factory.

Was the company doing tsunami evacuation drills at the time?

No, they weren’t.

So this place wasn’t a pre-determined evacuation area?

No, it was our first time going there. Our supervisor discussed it with the other managers, and they decided we would flee to that mountain. At that time they also prepared food and put it into backpacks.

What kind of food did you have?

It was canned food. The company makes canned goods, so that’s what we took.

Were there tsunami evacuation drills in the neighborhood you were living in?

No, there weren’t.

And so you didn’t know anything about evacuating, right?

I didn’t know anything, really. I hadn’t thought about it at all. I think my mindset has really changed from then to now, since the earthquake happened.

Two days at the assembly hall

What did the some-hundred employees do after evacuating to the mountain?

Some people gradually started heading home to check on their houses and families. Those who lived nearby went home on foot. I stayed at the assembly hall for two days. Other people from around the region also gathered there, and I hear some whose homes were washed away or destroyed stayed for around a month.

Did the assembly hall have running water?

No, it didn’t. Some other people went far away with their cars and brought us mountain water in tanks. We split it up amongst ourselves and used a little at a time as drinking water. For food, we had one meal a day. My coworkers and I ate canned food in the evenings. Two people shared one can. We were hungry and really tired.

Was the assembly hall large?

It was around 30 square meters, with two rooms around 15 square meters each.

And you were packed like sardines, right?

It was really full. There were no futons, either. The people in the houses behind us brought blankets and such, and we were really grateful. It was really cold, so we slept right up next to each other. There wasn’t even enough space to stretch our legs, so the whole time we had to sleep with our knees bent. We were still wearing our factory uniforms, so it was really cold.

What sorts of conversations did you have with your coworkers who were with you?

When I asked my coworkers what they were doing, I found out they were checking to make sure their families were okay. They said they wanted to go home because they were worried about their families. On March 12th I also said I wanted to go home, but I was stopped because a fire had broken out near the factory. Then on March 13th I walked to my daughter’s school with a coworker, and I was safely reunited with my daughter.

The day before that, on March 12th, one of my supervisors had asked me in writing, “What’s your daughter’s name? How old is she?” This person was going around asking this to everyone who had children, and taking notes. My supervisor walked to elementary and junior high schools a whole hour away on foot to check on the kids, and told the teachers, “Their mom is okay. Their dad is alive.” That person told me, “You daughter is well. She’s safe,” and I was really relieved.

How did you normally communicate with people at work?

In writing. I just happened to have a message board in my bag when the disaster happened, so I used that to communicate. If I hadn’t had paper, I may have had to manage with gestures, or just deal with not being able to communicate because I couldn’t say anything.

When you evacuated, did the people with you take you by the hand and lead you?

No. I had coworkers in front of and behind me, and I just followed the person in front.

Were there any other hearing impaired people besides you working at that company?

No, I was the only one. There was an intellectually disabled person there who also fled with us.

Living at the temple shelter

What did you do after you were reunited with your daughter on March 13th?

I wanted to go home to the prefectural housing complex with my daughter, but my coworker stopped me saying it was better not to go home, and that we should go to a nearby shelter. I didn’t know why myself, but my coworker knew that the electricity in our house was cut off, that there was no gas or running water, and that there was nothing to eat. They knew this information because they could hear. They used gestures to tell me “No water,” so I saw that and understood. Because I can’t hear, my coworker was worried about my daughter and I being alone and told me it would be better to go to a shelter. This coworker went with us to the shelter, introduced us, and explained our situation. The shelter was at a temple, and my daughter and I lived there for a while. I can’t get any information at all on my own, so I was really relieved when my coworker told me about the gas and electricity and went with me to the shelter.

Around how long were you at the temple?

For around a month and a half. Until the electricity came back on.

What kind of food did they give you?

Bread and rice balls and such. Oh, and there was also curry rice. The real kind with chicken in it. When I ate that, I knew they had really put their hearts into making it. It was so delicious that I said, “I’m full!” But there was still more, so it was actually a little too much for me. We also got lots of vegetables like lettuce, so we ate those too. We couldn’t cook things to eat often, so we ate lots of plain red leaf lettuce every day. There were snacks and drinks by the entrance of the main building, and those were free for everyone to eat. We also had newspapers, so we passed the time reading those.

Had a lot of people evacuated to the temple?

I hear there were around 100 people. To go to the bathroom, we had to take the flashlight sitting near the entrance of the main building where we were sleeping. There were lots of people sleeping with no space between each other, so I always worried I might step on someone, but I shuffled my feet as I walked.

What was the biggest problem you had while staying at the temple?

Right after I arrived at the shelter, there was a misunderstanding because the other people there didn’t know I couldn’t hear. One morning in particular was problematic. People were greeting each other saying, “Good morning,” and they thought I was ignoring them. These two old ladies gave me this look that seemed to say, “How rude! Young people should be more respectful,” and I thought, “I wonder what happened? This is weird.” So I asked the old woman next to me, “Did I do something wrong to those people?” She said, “Don’t let it get to you. Be strong,” and then I realized what was wrong. I thought, maybe these people don’t know I can’t hear, and maybe I have to tell them myself. So I wrote on paper, “I can’t hear. I’m sorry for not noticing your greeting before,” and showed it to the two old ladies the next morning. So then they said, “Oh really? We thought you could hear.” That dispelled the misunderstanding, and then we started laughing together and getting along. After that, they told everyone around us, “She can’t hear,” and people started tapping me on the shoulder when they wanted my attention. Those two old ladies really helped me. I realized it was important not to just wait around, but to take the initiative and tell people I can’t hear.

Did anything leave an especially good impression on you?

Some things were really hard at first, but once I told people I can’t hear, I guess I felt like I’d gotten a weight off my chest, and it became easier to communicate with people. I was really relieved. After that, I was able to live my life in peace. Communication was quite difficult at times, but I managed to correspond with people in writing.

What did you do about clothing and such? I imagine it would have been quite difficult to do laundry.

There was no water, so there was no way to do laundry. There was nothing else to do, so I wore the same clothes the whole time. It was impossible to take a bath, and my hair got all rough. There were also people who had no socks and had fled barefoot. There were a lot of people who looked cold, too.

We also couldn’t charge our cell phones, so I lent out my phone because it was fully charged, and after the generator came in late March, I lent out my charging cable and everyone used it. I didn’t want it to disappear, so I labeled it with my name.

A lot of relief supplies including clothing came from Tokyo and Osaka around the end of March. My daughter told me there was an announcement saying, “We’ve received women’s clothing. Please line up if you want something,” and the old lady next to me also said, “They’ve got good clothes for young people. Let’s line up together.” She gave me a lot of suggestions, like “You’re young, so red suits you.” It wasn’t really my style, haha, but I took what she suggested. I also saw other people forgetting about their difficult situation and chatting away, smiling and saying “You’d look good in this or that.” When something disastrous happens, people feel more positive if they know they’re in it together.

Returning home

Did you move to another place after the temple?

I went home when the electricity came back. Everyone was really happy when the power came on.

I was told the water would take another 2-3 months to come back on, but I also heard the Self-Defense Force was delivering water in trucks, so I went home. As long as I had electricity, I could communicate at night too. But I didn’t have any food, so I discussed what to do with the mother of one of my daughter’s classmates. I had her tell me in writing what she was doing about food, and at what time the water delivery trucks would come. Volunteers were making curry for us on Sundays, but I didn’t know that at first. My daughter just happened to hear about it, and so I took a pot to where everyone was going. I checked the time for the water trucks and lined up, but when the water ran out before my turn, I used gestures and such to find out when the trucks would come next. The gas in my house was LP gas, so I could use it, but I didn’t have access to a lot of water, so I couldn’t take a bath. Towards the end of March a friend came from Iwate by car and said, “Let’s have a bath and go out to eat together.” So my friend took my daughter and me to Iwate for a bath and a good meal.

The water finally came back on after around two months. After that we could take baths and cook meals.

Around how long after returning to your home did you get back to your normal routine?

I had lost my job, so things were tough for one or two years. I never went back to the life I had before. I think it really has changed completely. I used to be able to live my life without thinking much about it, but after the disaster all the roads to go shopping were closed or flooded, and I felt really insecure. I used to be able to talk and go drinking with my friends from the sign language club, but after the disaster I was so scared another earthquake might come that I couldn’t go out at night. After 2-3 years I finally got together with my friends again, but there was nothing left where there used to be a lot of houses, and it was hard for me because whenever I saw that I remembered the difficult experience I went through.

When it was time for my daughter to start high school, I discussed it with her and decided to move to Sendai, since I would need to start working again. My daughter seemed to be calmer after we moved and seemed to feel a lot better, so I was relieved. Both my daughter and I are feeling better now, although we’ve been through a lot.

Thoughts after experiencing the disaster

Do you feel like you’ve changed mentally or physically since experiencing the disaster?

Yes. I lost a lot of weight. My daughter did too. My daughter, who was in her first year of junior high school at the time, helped me with a lot of things, but she also panicked sometimes. What my daughter hated the most were the warning announcements. She got scared every time there was an announcement that water levels would rise or the roads would be blocked if it rained. Whenever there was an aftershock, we would immediately wake up, grab our things, and leave the house. It was really mentally exhausting doing that over and over.

We put a bunch of portable LED lamps and flashlights in our rooms to make sure we had lights when we went to bed so we could take those and immediately flee if something happened. We still have them now. Food, too. We still stock up even now.

So your disaster prevention awareness has increased. What were you doing to access emergency information before the disaster?

I accessed it through TV and my smart phone. I used apps and stuff. Whenever my daughter is gone at school or something, I can’t get any information orally, so I get it by watching my smart phone and the TV. When I’m out, I often think it would be nice if there were electric notice boards or something. In my case, I have to go ask people in writing what happened, or use my intuition to try to interpret what people around me are saying. If I keep asking over and over, after a while hearing people start to avoid talking around me because they don’t want to be rude, and then I start to feel bad about bothering them. I would be grateful if there was something I could see visually in addition to audio broadcasts.

After experiencing this disaster, do you have any advice or suggestions on preparations we should make for hearing impaired people?

I saw on the news about the Kumamoto earthquake that some families with hearing impaired members didn’t get information and missed food distributions for three days. I know the situation of each shelter is different, so if you’re hearing impaired I think it’s important to tell your neighbors you can’t hear, and although it might make you uncomfortable, you have to tell them with a smile. Rather than looking pained or disgruntled, if you just say, “Could you help me out?” people will say “Sure.” I heard one deaf person say, “When I’m the only deaf person surrounded by a bunch of hearing people, I tend to hold back and feel somehow ashamed.” One disabled person also said, “Putting abled and disabled people in separate rooms might also be a good idea.”

What sorts of things should hearing people be aware of when helping hearing impaired people?

Since you can’t identify a hearing impaired person by looking at them, I think it’s important for hearing impaired people to tell those around them that they can’t hear. You have to tell them yourself. But there are some people who don’t say anything. Of course this also depends on individual personalities. There are also some people who get frustrated, thinking, “No one helps me even though I can’t hear.” So I think it would be easier if supporters would start by writing on paper, “Is there anyone who can’t hear?” “Does anyone have a disability?” “Is anyone ill?” “Is anyone on medication?” They should check for these things first and then respond accordingly. I think it would be good if everyone could see and share this information before receiving support.

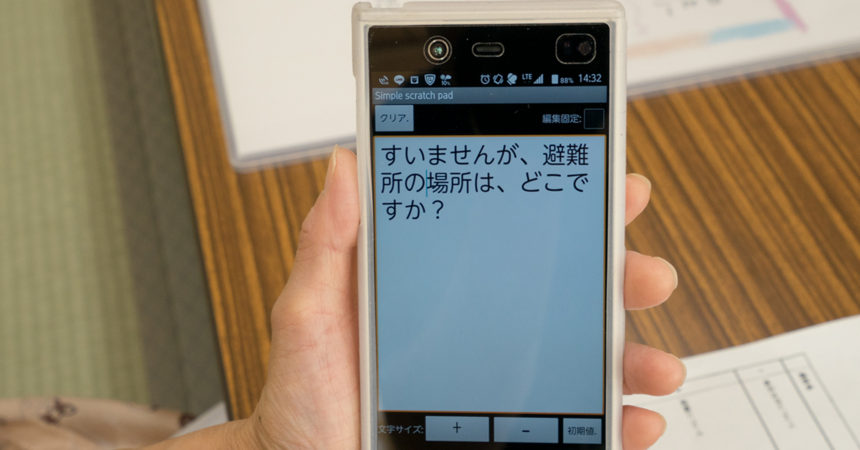

Is writing the simplest way to communicate with a hearing impaired person if you don’t know sign language?

Yeah, I think writing is best, but gestures are also effective.

Is there anything you want hearing people to know? Any requests?

Yes. Hearing people can listen to conversations or warning announcements to find out a tsunami is coming, but people who can’t hear don’t know. When an emergency happens, I would be grateful if hearing people would include hearing impaired people. Even just taking us by the hand or a piece of clothing is fine. Rather than acting of their own accord, I think hearing impaired people tend to evacuate by watching and imitating hearing people. If you don’t have any paper, you can make do by writing on your hand or using gestures or facial expressions to help hearing impaired people evacuate with you. It’s fine to split up after that. I’m talking about immediately after the disaster happens.

Then you also need flashlights. We can communicate by writing on paper or typing on a smart phone screen and showing it to hearing people. A flashlight is essential so we can help them see in dark places. Now there are convenient apps that enlarge the letters you type. When we don’t have anything to write on, we use smart phones and such to transmit and receive information. But when the battery dies, it’s over. When the battery gets low, you get anxious.